When two literature professors discover that a woman named María Lejárraga was behind some of the greatest Spanish literary works of the 20th century, they set out to learn why her name was omitted from history, and do everything in their power to restore her work to her name.

How to Listen

Listen free on Apple Podcasts or wherever you listen to podcasts.

Transcript

Martina: On a January morning in 1994, Juan Aguilera Sastre received a phone call from the president of a cultural centre called the Ateneo Riojano. She told Juan they were preparing an upcoming exhibit about an early 20th century Spanish author.

Juan: Ella me preguntó si quería participar en esa actividad. Yo le dije que por supuesto que sí, que el siglo XX me interesaba mucho y que iba a empezar a prepararme para el evento.

Martina: Juan was well known for studying Spanish writers and playwrights of the 1920s and 30s. So the cultural center assumed he would have plenty to say about the subject of the upcoming exhibit, a woman by the name María Lejárraga. But the name barely rang a bell…

Juan: El nombre no me era familiar. No era una autora reconocida de esa época. ¿Por qué iban a dedicarle un homenaje?

Martina: Juan consulted with another Spanish literature professor and linguist, Isabel Lizarraga. Conveniently, Isabel was sitting right next to him…because the two literature professors just happen to be married.

Isabel: Yo también enseño sobre los grandes autores del siglo XX de España, pero el nombre de María Lejárraga no me decía nada.

Martina: The couple asked the curator for more details. And that’s when they learned something shocking.

Juan: La presidenta del Ateneo dijo que probablemente ya habíamos leído muchos textos de María, pero con otro nombre. Ella creía que María Lejárraga tuvo que escribir usando el seudónimo de su marido, Gregorio Martínez Sierra.

Martina: Juan and Isabel were stunned. Gregorio Martínez Sierra was a well-known author in Spain. So to suggest that he hadn’t actually authored all of his work… It was a bold claim. They decided to investigate further.

Juan: Tuvimos que descubrir la verdad sobre María Lejárraga. En esa misión íbamos a descubrir que ella tenía una gran calidad intelectual, literaria… y feminista. Fue una de las figuras más importantes de la cultura española del siglo XX, pero cuando empezamos, muy pocos investigadores lo sabían.

Martina: Bienvenidos and welcome to a special season of the Duolingo Spanish Podcast. I’m Martina Castro, and this season we’re digging into some of the greatest mysteries of art and literature in the Spanish-speaking world.

As usual, the storyteller will be using intermediate Spanish and I’ll be chiming in for context in English. If you miss something, you can always skip back and listen again. We also offer full transcripts at podcast.duolingo.com.

Today, we travel to Spain to learn about one of the greatest writers of the twentieth century…whose identity is only just starting to be revealed to the public-at-large.

Keep an ear out for the accent from Spain, where the “c,” which usually sounds like an “s” sound, is pronounced with a “th” sound, so “inicia” sounds like “…inithia…”

Martina: Isabel and Juan knew a lot about Gregorio Martínez Sierra. He was a respected writer, poet, and theatre director in 1920s and 1930s Spain. He was especially renowned for the avant-garde plays he wrote, which were very successful at the time.

Juan: Por supuesto que había leído mucho sobre Gregorio Martínez Sierra y también había consultado su bibliografía para mi trabajo de investigación sobre la literatura de la época. Era un nombre muy conocido y una referencia de la época.

Martina: Some of Gregorio’s work made it all the way to Broadway…and got costume designs by Pablo Picasso himself.

Juan: Recibió muchas críticas positivas y tuvo mucho éxito con el público. A la gente dentro y fuera de España le gustaba su trabajo.

Martina: A few of Gregorio’s plays, like Canción de Cuna, or “The Cradle Song,” became so popular that they were even adapted into film.

Isabel: Canción de cuna habla de un grupo de religiosas que encuentran a una bebé abandonada en su convento. Ellas la cuidan hasta que crece y se casa. La obra tuvo tanto éxito que la adaptaron al inglés en Hollywood y se estrenó en español en Argentina.

Martina: This was all happening at a time when Madrid was a major European theatre hub…the epicentre of “show biz,” before film took hold as the most popular medium of mass entertainment.

Isabel: En esta época, Gregorio se convirtió en el Director del Teatro Eslava de Madrid. Ahí presentaron sus obras además de obras escritas por otros escritores famosos, como Federico García Lorca. Era un teatro muy importante.

Martina: But Gregorio’s theatre wasn’t just turning heads because of its high-profile collaborators. It was also pushing the boundaries for how women were represented in art at the time…challenging dominant narratives that painted women as submissive, or sometidas, and dependent on men. At the time, his work was groundbreaking.

Isabel: En ese entonces, las mujeres tenían poca independencia y vivían sometidas. Por esta razón, muchas de esas obras tienen el siguiente mensaje: Si la mujer quiere ser feliz, debe estudiar, emanciparse y no depender económicamente del marido.

Martina: An example of Gregorio’s groundbreaking representations of women is a play he published in 1911, called Primavera en Otoño, or Spring in the Fall. The premise of the story is unconventional, to say the least.

Isabel: La protagonista es una cantante de ópera que abandona su hogar para ser famosa. Ella deja a su marido con su hija y logra el éxito completamente sola. El mensaje de esta obra es muy importante porque en esos tiempos las mujeres vivían muy sometidas, tanto que ni siquiera tenían derecho a votar.

Martina: The more Isabel and Juan thought about Gregorio’s transgressive work…the more it seemed possible that it was indeed his wife, María Lejárraga, who had written the more feminist parts of it. But this was just a hunch. They had no proof…yet.

Juan: Sentía que valía la pena porque era un personaje importante que tenía muchas cualidades y una vida interesante. ¿Y si era ella la verdadera autora de las obras más transgresoras de Gregorio?

Martina: Together, Juan and Isabel began searching for answers. Their first stop was the library.

Isabel: Lo primero que hicimos fue ir a la biblioteca a buscar todo lo que ya se había escrito sobre María Lejárraga. Leímos los pocos libros que encontramos, no eran muchos.

Martina: As they began their research, Isabel and Juan got a little bit more context about María Lejárraga’s life. She was born in 1874 in the region of La Rioja, the same area where the cultural center Ateneo Riojano is located and where Juan and Isabel live.

Juan: Su padre era médico. Eran personas cultas y educadas, pero económicamente de clase media.

Martina: María Lejárraga was fortunate enough to get an education. She learned multiple languages, including French, Portuguese, Catalan, and Italian. This was extremely rare for the time, when literacy rates for women in Spain were only around 10%. After receiving an education, María went on to become a schoolteacher.

Juan: María era maestra y eso era algo excepcional porque, en esa época, había más maestros hombres que mujeres. Si eras mujer y tenías un trabajo, lo más probable era que trabajaras en casa de una familia, o en la agricultura, o en una fábrica…

Martina: Maria and Gregorio got married in 1900. During their first few years together, he was a struggling playwright, so María supported him financially.

Juan: Ella traía el dinero a la casa. Ganaba lo suficiente para vivir, pero no para tener muchos lujos.

Martina: Juan and Isabel read all these details during their research, but found no evidence in the official record that María might have been a writer herself. After reading hundreds of articles and books, they wondered if María Lejárraga had any living heirs who could fill in the gaps. They asked at the Ateneo Riojano, which seemed like a good place to start.

Juan: ¡Tuvimos mucha suerte! Nuestros colegas en el Ateneo Riojano nos pusieron en contacto con dos sobrinas de María Lejárraga que todavía estaban vivas en España. Ellas fueron muy amables. Nos dijeron que si necesitábamos algo, ellas nos podrían ayudar, así que decidimos reunirnos con ellas.

Martina: María Lejárraga’s nieces met with Juan and Isabel and told them that María never had children. So they were the ones in charge of maintaining her archives and keeping her memory alive.

Juan: Entre los documentos más importantes que tenían había varias cartas escritas por María Lejárraga.

Martina: While reading through María’s letters, Juan and Isabel got a big surprise… They learned that María Lejárraga had actually published one book under her own name in 1899, the year before she married Gregorio. But doing so enraged her family, to the point that she vowed not to publish anything under her name, ever again.

Isabel: Su familia no aprobó su primer libro llamado Cuentos breves. Por esa razón, después de aquella reacción tan negativa, ella decidió no poner su nombre en ningún otro libro.

Martina: But that wasn’t the only reason María stopped publishing under her own name. According to Isabel Lizarraga, Spanish society had little respect for women authors during this time in history. Writers like María had a better chance of getting their work published if they did so under a man’s name.

Isabel: Otra razón es que, en esos tiempos, ser escritora y firmar públicamente las obras era algo mal visto para las mujeres respetables en la sociedad española. Se consideraba una frivolidad y María no quería vivir esa situación.

Martina: But Maria was a writer at heart. She was determined to continue publishing…and as Juan and Isabel learned from her letters, she would write a lot more than just that one book from 1899.

Juan: En algunas de las cartas que leímos María Lejárraga decía abiertamente que era la autora de muchas de las obras de su marido, incluyendo Cartas a las mujeres de España.

Martina: According to María, a book called Letters to the Women of Spain, had been credited to Gregorio — when she was the one who wrote it. Juan and Isabel realized that this one piece of information, along with the letters they had read, could be the proof they needed to show that María Lejárraga was the real author of many of the plays, essays, and poems attributed to her husband. But there was more…

Juan: Cuando Gregorio murió en 1947, María intentó publicar sus obras completas con el nombre de los dos, María y Gregorio, pero no fue posible, y, por esta razón, no recibió el reconocimiento que merecía.

Martina: Maria Lejárraga’s nieces also told Isabel and Juan about a little-known memoir that she had written called Gregorio y yo. There she spoke freely about writing many of the works credited to her husband. She decided she did want some recognition, or reconocimiento, for her work. But once again, the norms of Spanish society conspired to keep her memoir out of the public eye…

Juan: Sus memorias se publicaron en México en 1953. Pero en España fue un libro prohibido. La dictadura de Franco no permitió su venta en España hasta el año 1975. Durante la dictadura, las mujeres no tenían libertad de asociación ni de expresión. Hubo muchos libros prohibidos.

Martina: One of the reasons María’s memoir remained hidden for so long was political. In the 1920s and 30s, María got involved in leftist and feminist politics. She even became a government representative for Spain’s Socialist Party. This did not last long. When the Spanish Civil War started in 1936, it changed her life forever.

Isabel: En ese momento el mundo de María Lejárraga cambió dramáticamente. Hacía varios años que Gregorio vivía con una actriz de su compañía aunque él y María seguían escribiendo juntos. En esa época, María se concentró en su misión política a favor de la República y de los derechos de las mujeres.

Martina: When Francisco Franco’s right-wing nationalist government came to power in Spain, many women in leftist politics, like María Lejárraga, were forced into exile. This was a government founded on traditional Catholic Spanish gender norms, and anyone who contradicted that was seen as a danger to national security.

Isabel: Cuando comenzó la Guerra Civil, María estuvo en peligro y tuvo que exiliarse. El tiempo pasó y ella fue olvidada.

Martina: As María was forgotten, or olvidada, Gregorio’s plays became less daring and controversial.

Isabel: María nunca quiso regresar a España durante la dictadura de Franco y permaneció en el exilio hasta su muerte en 1974.

Martina: Slowly, María Lejárraga’s contributions to politics, and her husband’s work, began to fade in Spain as the government censored any material that went against its cultural and political agenda. To Isabel, this was not surprising. She had grown up during Franco’s dictatorship, so she knew first-hand what it was like for women’s voices to be completely silenced.

Isabel: Nada de eso fue una sorpresa para mí porque en ese tiempo se esperaba muy poco de las mujeres. Ellas tenían que limitarse a ser amas de casa y madres de familia. Yo era una niña durante la dictadura de Franco, cuando las mujeres todavía no tenían voz.

Martina: Now that they had evidence that Maria Lejarraga was responsible for writing many of her husband's published works, Juan and Isabel decided to do something about it. First, they contacted other academics to raise awareness and make Maria’s name…widely known.

Juan: Isabel, otros profesores y yo investigamos mucho sobre María Lejárraga e inauguramos una calle con su nombre en la ciudad donde había nacido.

Martina: The naming of this street after María was a momentous event. So much so that María Lejárraga’s nieces were there for the naming ceremony, along with the mayor of the town.

Juan: Era la primera vez que una calle en España tenía su nombre. Después de eso, le pusieron su nombre a otras calles, bibliotecas y centros culturales en varias ciudades de España.

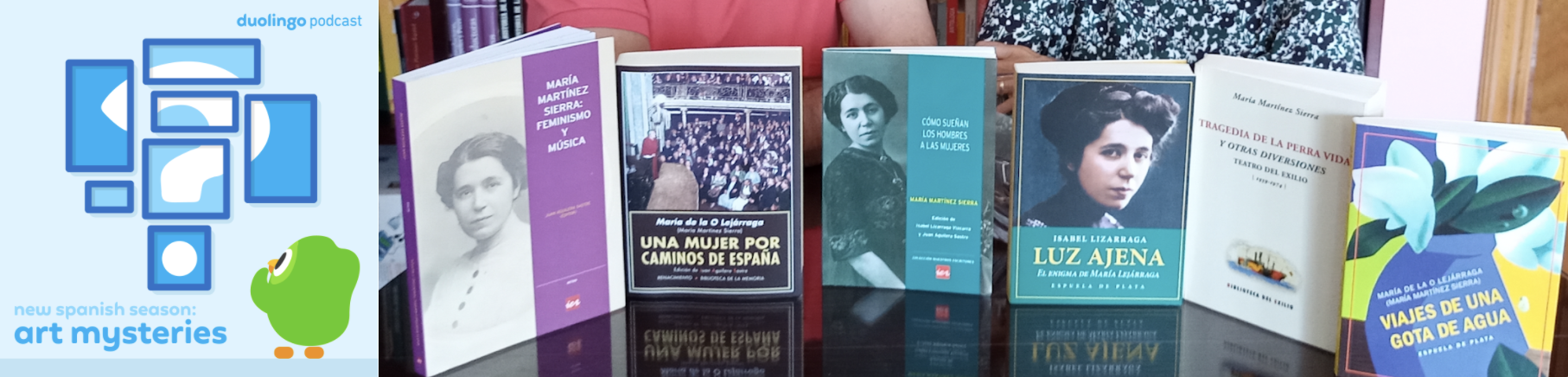

Martina: With the help of a Spanish publishing house, Juan and Isabel have edited and republished some of María Lejárraga’s work under her own name. Isabel has also written a novel aimed at the general public, based on María’s life. She thinks it’s important that people outside of academic circles know about María Lejárraga.

Isabel: La celebración en el Ateneo fue solo el primer paso; decidimos hacer más. Escribí una novela llamada Luz ajena. El enigma de María Lejárraga. Este libro es para que la gente que no esté interesada en la investigación filológica ni literaria, pueda conocer a esta mujer y su historia.

Martina: For Juan and Isabel, republishing María Lejárraga’s work under her own name — and writing books about her — is something that can be of value to the entire country.

Juan: María Lejárraga tiene la calidad y la categoría intelectual, humana, literaria y feminista para ser considerada como una de las figuras más importantes de la cultura española del siglo XX. Nuestra misión es simple: queremos que ella tenga el lugar que nunca debió perder por ser mujer. María Lejárraga todavía no es muy conocida, pero nosotros estamos trabajando día y noche para cambiar eso.

Martina: María Lejárraga is just one example of the many women writers who have been silenced or censored over the years. This episode is dedicated to all of them.

Juan Aguilera Sastre and Isabel Lizarraga Vizcarra live in La Rioja, Spain. Isabel’s novel, based on María Lejárraga’s life, is called Luz ajena: El enigma de María Lejárraga.

This story was produced by Adonde Media’s Caro Rolando.

We'd love to know what you thought of this episode! You can write us an email at podcast@duolingo.com and call and leave us a voicemail or audio message on WhatsApp, at +1-703-953-93-69. Don’t forget to say your name and where you’re from!

Martina: Here’s a message we recently got from Venice Bernard in Jamaica:

Venice Bernard: I've just finished reading your very fascinating story about Noemí Garía at Desideratum. I was fascinated to go on the journey with her, how she had her two passions and she united them and made financial…you know, a life out of it. I think it was wonderful. Loved it! Bye.

Martina: Thank you so much for taking the time to call us, Venice! We are so happy that Noemi’s story moved you as much as it did us.

If you liked this story, please share it! You can find the audio and a transcript of each episode at podcast.duolingo.com. You can also follow us on Apple Podcasts or your favorite listening app, so you never miss an episode.

With over 500 million users, Duolingo is the world's leading language learning platform, and the most downloaded education app in the world. Duolingo believes in making education free, fun, and available to everyone. To join, download the app today, or find out more at duolingo.com.

The Duolingo Spanish podcast is produced by Duolingo and Adonde Media. I’m the executive producer, Martina Castro. ¡Gracias por escuchar!

Credits

This episode was produced by Duolingo and Adonde Media.

![[Facebook]](./theme/images/share-facebook.svg)

![[Twitter]](./theme/images/share-twitter.svg)

![[LinkedIn]](./theme/images/share-linkedin.svg)