In 1973, 16-year-old Víctor Yáñez travels from his home in Chile to the former USSR to study agriculture. But when a military coup strikes at home, he's stranded in Communist Russia…for the rest of his life.

How to Listen

Listen free on Apple Podcasts or wherever you listen to podcasts.

Transcript

Martina: It was the fall of 1988, when Víctor Yáñez found himself listening to his radio in secret. In a tiny Russian town 2,000 miles from Moscow, Víctor and his friends were listening to one of the few American radio stations to reach the Soviet Union. Finally, the piece of news they were waiting for: the referendum in Chile.

Víctor: En la Unión Soviética no se hablaba de Chile porque era una dictadura de derecha. Los periódicos extranjeros estaban prohibidos. Era el año 1988 y todavía no había internet. Si querías saber de Chile, tenía que ser en secreto. Fue así como me enteré del referéndum.

Martina: When the results came in, Víctor was stunned. Through the static, he learned that 54% of Chileans had voted General Augusto Pinochet out of power. The dictatorship was falling. Although Víctor lived half a world away, the results had huge implications for him. As a Chilean, he would finally be able to go home.

Víctor: Yo había llegado a Rusia quince años antes, en un viaje de estudios durante el gobierno de Salvador Allende. Cuando empezó la dictadura de Pinochet, ya no pude volver a mi país. Yo había vivido la mitad de mi vida en Rusia, sabía muy poco de Chile y estaba lejos de mi familia. Ahora iba a tener la oportunidad de volver a casa, pero yo tenía una duda: "¿Cuál era mi país en realidad?".

*Martina:** Bienvenidos and welcome to the Duolingo Spanish Podcast. I'm Martina Castro. Every episode, we bring you fascinating true stories, to help you improve your Spanish listening, and gain new perspectives on the world.

The storyteller will be using intermediate Spanish, and I'll be chiming in for context in English. If you miss something, you can always skip back and listen again. We also offer full transcripts at podcast.duolingo.com.

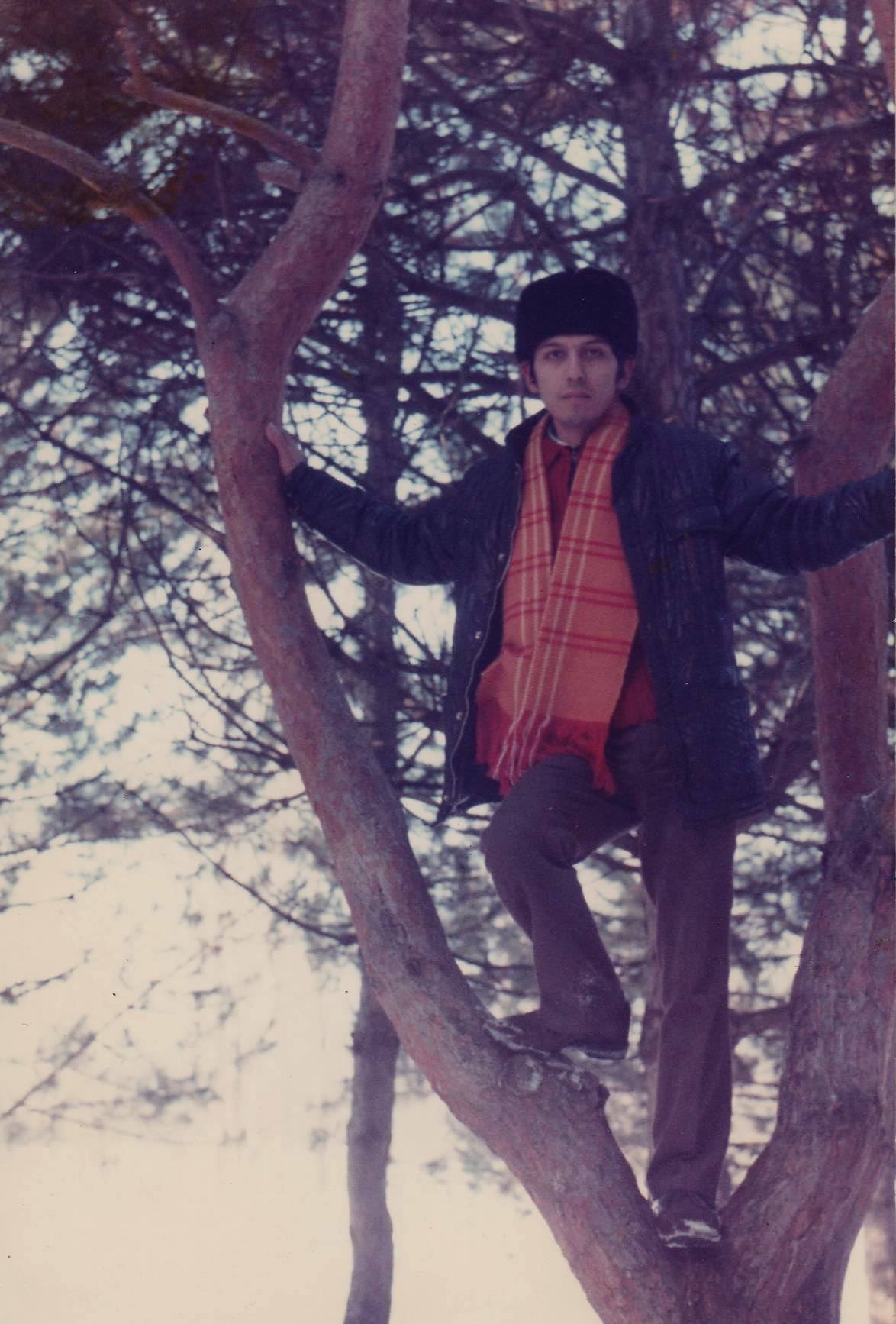

Martina: In September 1973, Víctor landed in Moscow for the first time, after an 18-hour flight with more than 90 other Chilean students. It was cold in Russia. Much colder than in Santiago, where spring was just arriving. But Víctor didn't care. He was 16, and it was his first time leaving Chile.

Víctor: Me sentí libre. Mi infancia en Chile fue muy difícil. Mi madre murió cuando yo era niño. Mi padre se volvió a casar y yo vivía con él, su esposa y mis hermanos menores. Yo no tenía una buena relación con mi padre porque él era muy estricto. Por esa razón, yo me quería ir de la casa. En el avión me sentía contento y pasé las horas cantando canciones con mis compañeros.

Martina: Víctor and his travel companions had been sent to Russia to study agronomy, the science of crops. They were on a full scholarship from the government of Chile. The socialist president, Salvador Allende was in office and, at the time, Chile and the USSR had close diplomatic ties. Víctor was the youngest in the group.

Víctor: Cuando llegamos, estuvimos una semana en Moscú e hicimos un poco de turismo. Visitamos el Teatro Bólshoi, que era muy bonito, y el mausoleo de Lenin. Todo me parecía nuevo y moderno. Yo sentía que había viajado al futuro.

Martina: After a week of sightseeing in Moscow, the students took a 16-hour train down to Ajtyrski, in the south of the country. This tiny and sleepy town, built during an oil boom, was meant to be their home for the next three years.

Víctor: Era un pueblo tranquilo con pocos habitantes y el clima era más caliente que en el resto de Rusia. Tenía una estación de tren. Antes había petróleo, pero ya no. Ahora solo había granjas.

Martina: Víctor and his schoolmates moved to a large, nondescript dormitory near their school. Soon, they met their new neighbors.

Víctor: Ellos eran muy amables, pero yo no hablaba ruso. Tres días después de llegar, conocimos a unos señores en un parque. Ellos intentaban decirnos algo que parecía importante, pero nosotros no entendíamos.

Martina: The Russians gestured urgently at Víctor and his friends. At one point, one of them formed a mock pistol with his hand. Víctor made out two words: "Salvador Allende." And then, "Pum, pum." It sounded like…gunshots, disparos.

Víctor: ¿Disparos? Mis amigos y yo corrimos a nuestro dormitorio. Allí, los profesores nos reunieron en una sala. Ellos intentaron explicarnos la situación, pero la comunicación era muy complicada porque los profesores no hablaban español y nosotros todavía no hablábamos ruso.

Martina: The room was buzzing with anxious students. It was difficult to understand anything. But Víctor was able to get an idea of what had happened: There had been a military coup in Chile. President Allende was dead. The general in charge, Augusto Pinochet, gave Chileans abroad 48 hours to return to Chile or stay out.

Víctor: Yo me sentía muy agitado. Cuarenta y ocho horas era muy poco tiempo. Algunos chicos gritaban, otros lloraban. Yo, simplemente… no tenía palabras.

Martina: None of the students were able to make it back in that 48-hour window. Their tuition, room, and board had already been paid. But for months, they weren't even able to get in touch with their families. Long-distance calls were a luxury. Letters went unanswered. Meanwhile, some Allende supporters in Chile were vanishing, or desapareciendo.

Víctor: Yo intenté escribirle una carta a mi padre, pero me la devolvieron cerrada. Mis compañeros tuvieron el mismo problema. Los intérpretes nos explicaron que Rusia y Chile habían cortado relaciones diplomáticas. El correo no llegaba. Y, además, en Chile, la gente que defendía el gobierno de Allende estaba desapareciendo.

Martina: It would be another two years before Víctor learned exactly what had happened to his family. His father, a proud communist, was arrested and held in jail for a year and a half. He eventually got out and fled to Panama with his wife and Víctor's brothers, Vladimir, Carlos Alberto, and Marcelo.

Víctor: Cuando mi papá llegó a Panamá, me pudo escribir. Desde entonces, a veces yo les escribía a mis hermanos y ellos me hablaban de sus vidas. Algunos de mis compañeros no supieron nada de sus familias. Fue muy difícil para ellos.

Martina: As the months went by, reality sank in. They were stranded in Russia. Many students were feeling hopeless. But somehow, for reasons he can't fully understand, Víctor wasn't. For him, sadness soon gave way to excitement.

Víctor: Yo no era feliz en Chile. La idea de comenzar una vida nueva en Rusia me emocionaba, pero había un gran problema… yo no hablaba ruso y no conocía las tradiciones ni las costumbres de Rusia. Era un extranjero en un país extraño y eso debía cambiar.

Martina: School went on as normal. As part of his program, Víctor had to do community service in a local kindergarten. While fixing furniture and painting walls, he realized that it was much easier to understand kids than adults. Their Russian was so much simpler!

Víctor: Yo hablaba mucho con los niños. Ellos me dijeron que los sábados por la mañana proyectaban películas para niños en el cine. Yo iba todas las semanas. Allí aprendí lo básico. En seis meses, yo ya hablaba bien y estudiaba mucho en el instituto. Yo era muy buen estudiante.

Martina: After conquering the language barrier, Víctor quickly settled into his new life in Russia. He made friends, fell in love, and got married young.

Víctor: Después de poco tiempo, conocí a Evguenia, una chica de la región. Nosotros nos casamos cuando ella tenía diecisiete años y yo, dieciocho. El director del instituto fue mi padrino de boda. Hicimos una gran fiesta en un gimnasio. Invitamos a todos mis compañeros de Chile y a la familia de Evguenia. ¡Eran casi 300 personas!

Martina: After graduating, Víctor was sent to work in a Kolkhoz. Kolkhozes, short for "collective ownership" in Russian, were large collective farms that were the cornerstone of the Soviet economic model. Víctor worked as an agricultural mechanic at a kolkhoz that produced rice.

Víctor: Yo trabajaba mejorando la producción de arroz en el koljós. Me gustaba mucho ese trabajo. Yo vivía ahí con Evguenia y nuestro hijo, Rodemil.

Martina: To Víctor, Russia was feeling more and more like home. Soon, even things that Víctor had first found unsettling about the country felt comforting and familiar. For example, borscht, a soup made from beets, or remolachas.

Víctor: En nuestro primer día en Rusia, nos llevaron a una cafetería y nos sirvieron una sopa de remolacha. Se llamaba borscht. ¡Nunca había probado algo tan malo! Y yo no era el único que pensaba eso porque a nadie más le gustó.

Martina: But over time, something funny happened. That same beet stew that Víctor had initially found so repulsive, eventually became one of his favorite Russian foods.

Víctor: El borscht que preparaban las mujeres que trabajaban en mi koljós (con ingredientes frescos de la granja) era completamente diferente. ¡Me pareció delicioso!

Martina: As Víctor felt more and more at home in Russia, he noticed his memory of Chile — his homeland, or patria — was fading deeper into the corners of his mind. But every once in a while, he'd get a letter from his father or siblings, and the memories would come flooding back.

Víctor: Yo sí sentía nostalgia cuando pensaba en Chile, en mis hermanos y en el mar. Siempre pensé que Chile era mi patria, pero la había dejado muy joven y ya llevaba quince años fuera del país. Las cosas habían cambiado mucho y yo era feliz en Rusia. Cuando escuché que la dictadura de Pinochet había terminado, no estaba seguro de si quería volver a Chile.

Martina: By 1988, Víctor had a full life in Russia: a meaningful job, a home, and family. So that day with the radio, when he learned about Augusto Pinochet's fall from power, he was torn. He'd been in Russia for 15 years. Now he finally had the chance to go home…but he wasn't sure he wanted to.

Víctor: Pasaron unos cuantos años y, en 1991, Mikhail Gorbachev, el último líder soviético, renunció a sus funciones. Era el final de la Unión Soviética y de la vida en Rusia como yo la había conocido. Todos los koljós comenzaron a cerrar uno por uno, incluso el mío.

Martina: For Víctor and his family, the end of the collective farm system was the start of hard times. He was forced to move to the industrial city of Krasnodar and take a job in a metal parts factory. It was hard work, with low pay.

Víctor: Era un trabajo muy duro. El dinero que ganaba como obrero a veces no era suficiente para comer. A menudo, yo pensaba en ahorrar dinero para comprar un pasaje de avión e ir a Chile, pero era imposible. ¡Era demasiado caro!

Martina: Víctor struggled for many years. He went from factory job to factory job. He got divorced, remarried and had two more sons. But something in particular worried Víctor: over time, even as he continued to write to his father and brothers, he could feel his Spanish start to slip away.

Víctor: Un día, yo le estaba escribiendo una carta a mi padre. Escribí: "Querido papá". De pronto, estaba buscando una palabra, ¡pero no podía recordarla! Solo me la sabía en ruso, pero no me salía en español. Fui a buscarla a un diccionario y era algo como "departamento", una palabra muy simple. ¡Estaba olvidando el idioma de mi país!

Martina: So Víctor came up with a solution. There was a library in Krasnodar that had a Spanish-language section. They were cheap paperbacks, but they contained all the classics by Latin America's great authors: Gabriel García Márquez, Pablo Neruda… And Víctor devoured them all.

Víctor: Yo los leí todos. Me quedaba en la biblioteca hasta tarde en la noche. Como hice cuando era joven, volví a aprender un idioma rápidamente gracias a un trabajo duro.

Martina: There was a reason Víctor was determined not to lose his Spanish. He continued to toy with the idea of visiting his family, who’d finally been allowed to return to Chile from Panamá. But somehow, years turned into decades. Until one day, Víctor got some sad news.

Víctor: Un día en el 2010, Vladimir, uno de mis hermanos, me llamó por teléfono y me dijo que mi padre había muerto. Al menos él pudo decirle adiós a su país.

Martina: Even though Víctor and his Dad had not been especially close, in moments like these the distance weighed on him. He realised that he longed to see Chile again…

Víctor: Me di cuenta de que sí quería volver, pero el problema era el costo del viaje. Yo quería regresar a Chile, pero todavía no podía hacerlo. Entonces, poco a poco, empecé a ahorrar dinero.

Martina: Víctor continued to keep in touch with his brothers, especially Carlos Alberto. Letters turned into emails, then Skype calls. In 2018, Víctor turned 60. Finally, on the cusp of retirement, he could afford to pull together the money for the long distance flight.

Víctor: A los sesenta años, me jubilé y empecé a recibir una pensión. Mis hijos eran adultos y ya no necesitaban mi ayuda económica. Empecé a ahorrar dinero y a coordinar las fechas con mis hermanos. Después de casi un año, finalmente pude comprar mi pasaje de regreso para Chile.

Martina: In 2019, 45 years after leaving Chile for what was supposed to be a temporary study abroad trip, Víctor was finally going home. His brother Carlos Alberto promised to pick him up at the airport in Santiago.

Víctor: Yo estaba muy emocionado. No había visto a Carlos Alberto desde que tenía dieciséis años. También iba a ver a Vladimir y a Marcelo, mis otros dos hermanos.

Martina: After landing, Víctor hauled his two heavy suitcases off the conveyor belt and exited baggage claim. He anxiously scanned the sea of faces waiting to receive their loved ones outside. It had been so many years. Suddenly, he heard his name.

Víctor: Escuché: "¡Víctor, Víctor!", y ahí estaba Carlos Alberto. Lo reconocí inmediatamente. Nos abrazamos durante cinco minutos. ¡Casi no me dejaba respirar! Yo no soy una persona sentimental, pero, ese día, los dos lloramos.

Martina: After the first wave of emotions subsided, Carlos Alberto took his brothers back to his apartment in La Cruz, about two hours west of Santiago. There, a traditional Chilean feast awaited them, including cazuela — a rich beef stew — and pastel de choclo — a corn casserole.

Víctor: No había probado ese tipo de comida en más de cuarenta y cinco años. ¡El sabor me pareció increíble! En ese momento sentí mucha nostalgia por el país que me vio nacer. Estaba muy confundido. A lo mejor, esta era mi casa y no Rusia. ¿Y los últimos cuarenta y cinco años de mi vida? ¿Acaso había sido simplemente un accidente que me llevó de regreso a mi país?

Martina: After dinner, Víctor and his brothers sat talking, laughing, and reminiscing into the early hours of the morning. The next day they took a tour across Chile, visiting long-lost relatives and friends. The first stop was Valparaíso, the coastal town where the brothers grew up.

Víctor: Valparaíso había cambiado mucho. Regresar fue un golpe enorme. Cuando yo me fui, había casas de cuatro pisos como máximo, pero cuando regresé vi edificios de veinte, veinticinco y treinta pisos por toda la costa. Fue como cuando llegué a Moscú la primera vez, ¡sentía que había viajado al futuro!

Martina: Though some parts of his former hometown looked the same, like the historic main plaza and the old docks, much of it was unrecognizable to Víctor. Coming back felt strange. He was happy at times, but also sad.

Víctor: Sentí mucha emoción. Yo no conocía a la mayoría de mis familiares, pero me hicieron sentir parte de la familia. ¡Estaba muy feliz!

Martina: Surrounded by family and friends, Víctor's heart was full. And yet, in the back of his mind, he felt this vague sense of unease…sadness, even. It was hard to put his finger on it, but eventually, Víctor understood what the feeling was: homesickness.

Víctor: Después de pensarlo mucho, llegué a la siguiente conclusión: a mí me hacía falta el idioma… el ruso. Me hacía falta escucharlo en la calle y hablarlo con la gente. Yo creo que después de cuarenta y cinco años se volvió parte de mí.

Martina: For so many years, living in Russia, Víctor had considered himself a Chilean in a foreign land. But his trip back to his home, or hogar, taught him something very different.

Víctor: Antes de mi viaje, yo sentía que Chile era mi patria y que Rusia era mi hogar adoptivo. Sin embargo, mi viaje de regreso a Chile me demostró algo muy importante: ahora yo tengo dos hogares y los amo por igual. Al final de mi viaje, estaba muy feliz de regresar a mi casa.

Martina: Víctor Yáñez is a retired mechanic living in Krasnodar, Russia. He is planning another trip back to Chile in 2021, and this time, he plans to take his sons with him.

This story was produced by Adonde Media's Lorena Galliot.

We'd love to know what you thought of this episode! You can call and leave us a voicemail or audio message on WhatsApp, at +1 703 953 93 69, or write us an email at podcast@duolingo.com. And if you liked this story, please share it! You can find the audio and a transcript of each episode at podcast.duolingo.com. You can also subscribe at Apple Podcasts or your favorite listening app, so you never miss an episode.

With over 300 million users, Duolingo is the world's leading language learning platform, and the most downloaded education app in the world. Duolingo believes in making education free, fun, and accessible to everyone. To join, download the app today, or find out more at duolingo.com.

The Duolingo Spanish Podcast is produced by Duolingo and Adonde Media. I’m the executive producer, Martina Castro. ¡Gracias por escuchar!

Credits

This episode was produced by Duolingo and Adonde Media.

![[Facebook]](./theme/images/share-facebook.svg)

![[Twitter]](./theme/images/share-twitter.svg)

![[LinkedIn]](./theme/images/share-linkedin.svg)