When a young attorney from Chad decided to take on the ex-dictator who terrorized her country, she knew she was going up against dark and powerful forces. But that didn’t stop her from dedicating her life to fighting for justice in her homeland.

How to Listen

Listen free on Apple Podcasts or wherever you listen to podcasts.

Transcript

Ngofeen: Hey everyone, a quick word before we begin: today’s episode is about the fight to bring a dictator to justice for his crimes against humanity. There are no graphic scenes in this episode, but in order for our narrator to share her story fully, she refers to acts of sexual violence.

Ngofeen: 1982 was the year that Jacqueline Moudeïna’s life changed forever. She was 22, came from a prominent family of intellectuals in the country of Chad, and was married to a well-respected political journalist.

Jacqueline: Dans les années avant 1982, je faisais des études de langues à l’université de N’Djamena, la capitale. Je voulais devenir interprète. Hissène Habré était Premier ministre à l’époque.

Ngofeen: Hissène Habré was a rebel leader who seized power in Chad in June of 1982. He formed a dreaded secret police, known as the DDS, which persecuted political opponents and intellectuals. Like many Chadians, Jacqueline and her husband were forced to flee to another country in Africa. They sought refugee status in the nearby Republic of Congo.

Jacqueline: J’ai laissé derrière moi ma maison, les gens que j’aimais, et tout ce que j’avais. Je ne savais pas quand j’allais pouvoir revenir. Autour de moi, il y avait beaucoup d’autres réfugiés du Tchad. Il y avait des enfants seuls, des orphelins. Ils pleuraient. Moi aussi, j’avais perdu mes parents quand j’étais petite. Pour moi, entendre les orphelins pleurer, c’était insupportable.

Ngofeen: As Jacqueline scanned the crowd of refugees, she was filled with rage against the man who had forced all these people to leave their country. In that moment, she had never felt more powerless. It would be another 16 years before she returned home to Chad, but when she did, she would make it her mission to seek justice against Hissène Habré.

Jacqueline: Pendant que j’étais au Congo, j’ai décidé de faire des études de droit. Quand j’ai enfin pu rentrer au Tchad, j’étais devenue avocate. Et j’étais déterminée à me battre pour la justice dans mon pays.

Ngofeen: Bienvenue and welcome to the Duolingo French Podcast. I’m your host, Ngofeen Mputubwele. Every episode, we bring you fascinating true stories to help you improve your French listening and gain new perspectives on the world.

The storyteller will be using intermediate French, and I’ll be chiming in for context in English. If you miss something, you can always skip back and listen again. We also offer full transcripts at podcast.duolingo.com.

In this episode, you’ll notice that Jacqueline speaks French with a Chadian accent, meaning her Rs sound more rolled, like when she says “Hissène Habré.”

Jacqueline: Hissène Habré.

Ngofeen: Hissène Habré was deposed in 1990 after eight years in power. He fled to Senegal that same year, but Jacqueline didn’t return to her home country until 1995. When she finally moved back to Chad, the wounds from Habré’s reign of terror were still fresh.

Jacqueline: Au Tchad, tout le monde connaissait quelqu’un qui avait été en prison ou qui avait disparu sous le régime d’Hissène Habré. Une commission indépendante a découvert que presque 40 000 personnes étaient mortes ou disparues pendant le régime d’Habré.

Ngofeen: Jacqueline passed the bar exam in Chad, and became an attorney. She also volunteered as the legal secretary of one of Chad’s most prominent human rights groups, the Chadian Association for the Promotion and the Defense of Human Rights.

Jacqueline: Avec mes collègues de l’Association pour la Défense des Droits de l’Homme, on parlait beaucoup d’Hissène Habré et de tous les crimes qu’il avait perpétrés.

Ngofeen: Meanwhile, in Senegal, Habré was living in lavish accommodations, free of consequence. Jacqueline couldn’t stand this level of impunity.

Jacqueline: Pour moi, voir Hissène Habré libre, c’était insupportable. À cause de Habré, des milliers de Tchadiens ont souffert. Mais lui, il vivait comme un roi. Il fallait que ça change. J’ai dit : « S’il reste en liberté, c’est une injustice. Il faut l’amener devant un tribunal. »

Ngofeen: Bringing Hissène Habré himself to trial. It was a crazy idea. Chad’s legal system was recovering from years of dictatorship. Members of Habré’s former government were still in power. But one day, in late 1998, the group’s president came to see Jacqueline.

Jacqueline: La présidente m’a dit : « Jacqueline, tu es une jeune avocate, mais tu es excellente. Est-ce que tu acceptes de prendre le dossier Habré, pro bono ? » Bien sûr, j’ai accepté. C’était un choix évident pour moi.

Ngofeen: Jacqueline’s organization decided to mount a legal case against Hissène Habré. The first thing they had to do was find survivors willing to step forward. At the time, most Chadians were still afraid of Habré and his supporters. But one small group of survivors, led by a man named Souleymane Guengueng, had begun to speak out.

Jacqueline: Je rencontrais les victimes à mon bureau et je leur demandais de me raconter leurs histoires. Beaucoup de victimes ne voulaient pas parler de ces choses. Ces gens avaient été torturés. Ils avaient vu des gens mourir. Mais c’était important de documenter la vérité.

Ngofeen: Jacqueline knew that under international law, cases involving torture can be considered crimes against humanity. To her, it was vital that the atrocities that occurred in Chad under Habré’s regime be internationally known, and prosecuted.

Jacqueline: Je disais aux victimes : « Le monde doit savoir ce qu’il s’est passé. Il faut une justice. Votre voix va aider à faire la justice. »

Ngofeen: Jacqueline encouraged the survivors to talk about what they had endured. Under her careful questioning, person after person found the strength to share their stories. Some even opened up about the most taboo of crimes: sexual violence and rape, le viol.

Jacqueline: Je savais qu’il y avait eu des viols dans les prisons de Habré. Mais pendant longtemps, personne n’en parlait directement. Le viol est un tabou très fort au Tchad. Personne n’en parle. Souvent, c’est un crime qui reste sans conséquence. Pour moi, c’était inacceptable.

Ngofeen: For over a year, Jacqueline continued to gather evidence and interview survivors. Her organization joined forces with Human Rights Watch and other human rights groups, forming a loose coalition to strengthen the case against Habré. In 2000, the coalition was finally ready to file their claim in court, porter plainte.

Jacqueline: Sept victimes étaient prêtes à porter plainte. On avait beaucoup de preuves pour confirmer leur histoire. On a déposé une plainte dans un tribunal au Sénégal. C’est là-bas que Habré s’était exilé. Au même moment, on a déposé une autre plainte au Tchad, contre plusieurs complices de Habré.

Ngofeen: At first, both claims seemed promising: a judge in Senegal had indicted Habré for crimes against humanity. But Habré had powerful connections in the Senegalese government, and they put pressure on the court. Just five months later, an appeals judge dismissed the indictment and threw out the case.

Jacqueline: J’étais très déçue. Au Tchad, la plainte contre les complices de Habré n’a pas eu de résultats non plus. Les tribunaux du Tchad et du Sénégal n’étaient pas assez indépendants. Il y avait beaucoup de corruption. On avait besoin d’un tribunal vraiment indépendant.

Ngofeen: There’s a principle in international law called universal jurisdiction. What it means is that crimes against humanity can be tried in an independent international court, regardless of where the crimes were originally committed. So Jacqueline and her allies began lobbying for a special international court to hear Habré’s case. That’s when the threatening phone calls began.

Jacqueline: J’ai commencé à recevoir des appels téléphoniques anonymes. Chaque nuit, mon téléphone sonnait. J’entendais la voix d’un inconnu. Il me disait : « Si tu veux vivre, tu dois abandonner ce dossier. »

Ngofeen: Jacqueline didn’t tell anyone about the anonymous threats. She refused to let herself be intimidated. In 2001, she even helped organize a peaceful women’s march in front of the French embassy in Chad.

Jacqueline: Le 11 juin, j’ai participé à une marche pacifique des femmes, devant l’ambassade de France au Tchad. C’était très risqué, parce que les manifestations étaient interdites par le gouvernement. Quand on est arrivées à l’ambassade, les autorités nous attendaient. Il y avait plusieurs unités de police, la garde présidentielle, et même des militaires.

Ngofeen: Jacqueline recognized the man heading up all the units. He was one of Habré’s accomplices, one of the people listed in the complaint filed by Jacqueline and her team.

Jacqueline: Ce n’était pas bon signe. Mais je ne voulais pas partir. J’ai dit aux femmes dans mon groupe : « Surtout, restez calmes. Ne faites pas de mouvements brusques. »

Ngofeen: Jacqueline and her companions sat in front of the embassy in quiet protest. Slowly, the policemen and the soldiers started to form a circle around them. Then Jacqueline saw a hand rise up in the air, as if to give a signal. Immediately afterwards, she noticed a small object hurtling towards her.

Jacqueline: J’ai vu la grenade avant son explosion. Je l’ai vue voler vers moi, elle tournait dans les airs. Je voulais me lever, mais je ne pouvais pas. J’avais très peur.

Ngofeen: As Jacqueline scrambled to get up, the grenade landed at her feet. Then, after a few seconds that felt like an eternity… it exploded. After the grenade attack, Jacqueline was rushed to the hospital. She remained hospitalized for 15 months. Jacqueline knew she’d been targeted because of her involvement in the lawsuit against Habré. But knowing this only made her more determined to seek justice.

Jacqueline: Pour moi, l’attentat a été comme un stimulant. Ça m’a encouragée à continuer. À l’hôpital, je me disais : « Quand je pourrai me lever, je reprendrai mon dossier ! »

Ngofeen: Jacqueline’s family was horrified. They tried to convince her how dangerous it was for her to continue with the lawsuit.

Jacqueline: Personne n’était d’accord avec moi. Mais moi, je disais à tout le monde : « Vous ne pouvez pas comprendre ce que je fais. Pour moi, c’est une mission de Dieu. Certaines personnes ne peuvent pas s’exprimer. Moi, je dois me battre pour elles. »

Ngofeen: So Jacqueline got back on her feet and back to work on the case. In 2004, she became president of her human rights organization, and along with the other rights groups in their coalition, they kept pushing for the creation of a special court in Senegal. It was a long process that took years.

Jacqueline: On est allés voir tout le monde : les Nations Unies, la Cour Internationale de Justice, à La Haye et l’Union Africaine. On a organisé des rencontres entre des victimes et des hommes politiques, au Sénégal et en Europe, pour influencer l’opinion publique. Ce travail a duré des années.

Ngofeen: In 2012, after a decade of international and political pressure, Senegal finally agreed to create a special tribunal, une cour, with funding from the international community. Three independent African judges were assigned to preside over it. This was the moment Jacqueline and her allies had been waiting for.

Jacqueline: On attendait avec impatience la création de cette cour. Puis, mes collègues et moi, nous avons déposé une nouvelle plainte.

Ngofeen: If Jacqueline and her colleagues succeeded in their case, it would be the first time a former head of state was convicted of human rights abuses inside a special African tribunal.

Jacqueline: Dans notre plainte, mes collègues et moi avons mis tous les résultats de nos années de recherche. Nous y avons mis aussi une longue liste des victimes.

Ngofeen: During the many years of investigation, Jacqueline had continued to meet with Habré’s victims, gathering their stories so that some of them could one day testify against Habré, témoigner contre Habré. The stories that haunted her the most were those of the survivors of sexual violence.

Jacqueline: Ces femmes me racontaient ce qui leur était arrivé. Ça me rendait malade, physiquement malade. Mais pour moi, c’était très important que ces femmes acceptent de parler au tribunal, pour témoigner contre Habré. Je savais qu’elles auraient un impact très important. Mais il fallait qu’elles parlent.

Ngofeen: But the women were scared. In their communities, rape is a major taboo, and survivors can face real stigma. It was one thing to tell Jacqueline their story, but taking the stand? Speaking out in public? That seemed impossible.

Jacqueline: Elles me disaient : « Ce n’est pas possible, et tu le sais. Il faut que toi, tu trouves les mots pour raconter notre histoire aux juges. »

Ngofeen: Shortly before the trial, Jacqueline gathered a small group of women in her office. One by one, she told them that their voices were important. That they could help take down Habré. And that there was nothing to fear.

Jacqueline: J’ai dit à ces femmes : « Vous avez déjà vécu l’horreur. Moi aussi, j’ai vécu des choses très difficiles. Mais nous sommes là. Nous ne sommes pas mortes. Un jour, la mort vient pour tout le monde. Mais ce qui est important, c’est de se battre quand on est vivant, pour empêcher l’horreur. Vous devez vous battre, pour vos enfants et vos petits-enfants. »

Ngofeen: She told them “fight for your children and your grandchildren, so that they won’t experience what you lived through.” And the women listened thoughtfully. Finally, several of them said they would consider taking the stand at trial.

Jacqueline: Quand ces femmes ont pris courage, ça m’a donné de l’espoir. C’est pour ça que je me battais depuis toutes ces années.

Ngofeen: In July 2015, the day Jacqueline had been fighting for for so long finally came. Habré was being brought to trial for his crimes. Still, many challenges remained. Habré was in custody, but he and his lawyers refused to recognize the legitimacy of the court.

Jacqueline: Je me demandais si ce procès était réellement possible. J’essayais de garder espoir. Le jour du procès, on est entrés dans le tribunal. Habré n’était pas encore assis à sa place.

Ngofeen: Habré had refused to leave his holding cell. He had declared he would not appear in court. There was a tense silence in the courtroom as the three judges deliberated on what to do. Finally, they made a decision: Habré would come to court, by force if necessary. They sent four guards to get him. It’s all captured on tape.

Jacqueline: Habré est entré dans la salle en criant. Les gardes l’obligeaient à avancer. Il refusait d’être là. Je l’ai vu entrer dans la salle. Les gardes l’ont forcé à s’asseoir et les juges lui ont demandé de se taire. Alors, j’ai pensé : « Ce procès va enfin devenir réalité. »

Ngofeen: The trial was finally underway. But Jacqueline was nervous. Her team was planning to fly in several women from Chad to Senegal to testify against Habré, and she knew how frightened they were. They were watching the trial proceedings on live TV back in Chad, and they were petrified. So, Jacqueline flew to Chad to meet with them.

Jacqueline: Je les ai réunies dans mon bureau. Elles me disaient : « On ne peut pas parler. On ne peut pas apparaître à la télévision. Nos enfants et nos petits-enfants vont nous voir. » J’ai répondu : « Les juges et le monde doivent entendre votre voix. Vous méritez d’être entendues. »

Ngofeen: Jacqueline convinced the women to fly back with her to Senegal. The night before they were due to take the stand, she stayed with the women until midnight, trying to reassure them. The following morning, Jacqueline stood in front of the judges as the first woman was called to the stand. Slowly, a judge began to question the first woman.

Jacqueline: Je ne savais pas du tout ce qui allait se passer.

Ngofeen: The woman on the witness stand looked at Habré, sitting silently in his chair. She looked at the three judges, and she began to talk. Here’s a recording from that day.

Jacqueline: Elle a raconté toute son histoire, du début jusqu’à la fin : la déportation, les tortures, les viols. Je ne pouvais pas le croire. Une par une, les femmes sont venues et elles ont parlé de leurs histoires. Elles ont eu beaucoup de courage. Quand elles ont vu la cour et les juges, je crois qu’elles ont compris que c’était important de parler. Pour faire la justice.

Ngofeen: The women’s testimony was a turning point in Habré’s trial. And it was also a pivotal moment for the women themselves. Habré had been an all-powerful dictator. Now, he was in a courtroom, sitting in silence. And their voices were being heard.

Jacqueline: Ce jour-là, les victimes ont arrêté d’avoir peur. Une des femmes a dit qu’elle se sentait très fière et très courageuse, parce qu’elle était devant Habré, et qu’elle pouvait parler de son histoire. Quand j’ai entendu ça, je me suis sentie très fière, moi aussi.

Ngofeen: After months of witness testimony and deliberations, the court found Hissène Habré guilty...

Male voice: ...accusé de crimes contre l’humanité, crimes de guerre et crimes de torture.

Ngofeen: ...of crimes against humanity, war crimes, and torture, including sexual violence and rape.

Male voice: Hissène Habré, la chambre vous condamne à la peine d’emprisonnement à perpétuité.

Ngofeen: He was sentenced to life in prison and ordered to pay 145 million dollars in survivor compensation.

Male voice: L’audience, ainsi, est levée. Merci.

Jacqueline: Le jour du verdict a été une victoire énorme ! On avait gagné. La justice reconnaissait enfin la souffrance des victimes que je représentais. La voix de ces femmes était enfin entendue.

Ngofeen: The verdict against Hissène Habré was a historic moment—not just for Chad, but for the international human rights community as well. It was the first time a former head of state was convicted of human rights abuses inside a special African tribunal. It was a historic moment as well, for Jacqueline.

Jacqueline: Ce verdict, c’est la preuve que personne n’a le droit de commettre des crimes sans être puni, pas même un ancien chef d’État. Pour moi, c’est une fierté immense. C’est le travail de toute une vie.

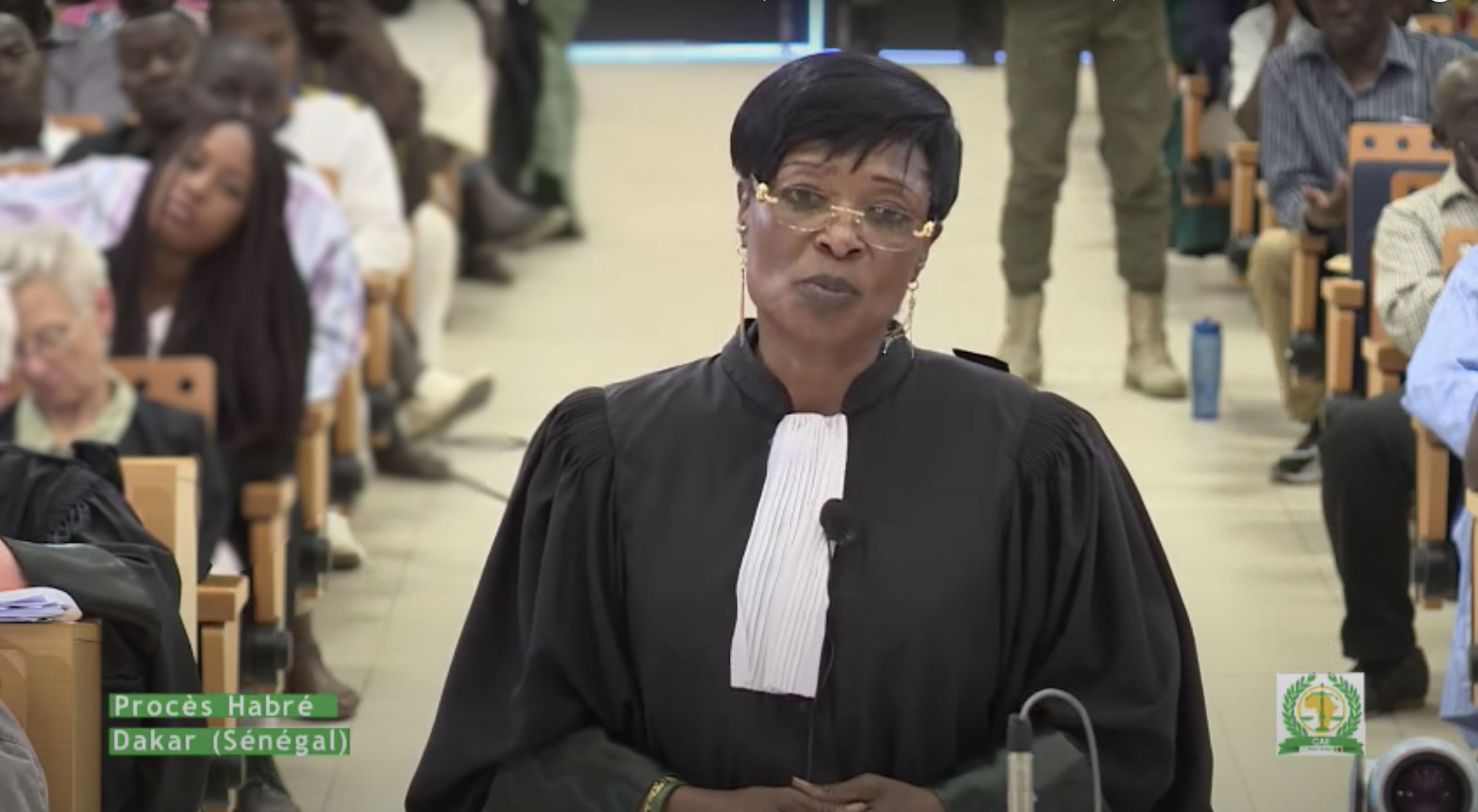

Ngofeen: Jacqueline Moudeïna is a human rights lawyer living in N’Djamena, Chad. She is president of the Chadian Association for the Promotion and the Defense of Human Rights, ATPDH in French. She continues to fight alongside the survivors of Habré’s regime, who to this date have still not received the compensation ordered by the court.

This story was produced by Adonde Media’s Lorena Galliot.

We’d love to know what you thought of this episode! Send us an email with your feedback at podcast@duolingo.com. And if you liked the story, please share it! You can find the audio and a transcript of each episode at podcast.duolingo.com. You can also subscribe at Apple Podcasts or your favorite listening app so you never miss an episode.

Duolingo is the world's leading language learning platform, and the #1 education app, with over 300 million users worldwide. Duolingo believes in making education free, fun, and accessible to everyone. To join, download the app today, or find out more at duolingo.com.

The Duolingo French Podcast is produced by Duolingo and Adonde Media. I’m your host, Ngofeen Mputubwele, à la prochaine!

Credits

This episode was produced by Duolingo and Adonde Media.

![[Facebook]](./theme/images/share-facebook.svg)

![[Twitter]](./theme/images/share-twitter.svg)

![[LinkedIn]](./theme/images/share-linkedin.svg)