In 2013, a Peruvian photographer visits his parents’ village and unexpectedly becomes dedicated to improving literacy in rural Peru.

How to Listen

Listen free on Apple Podcasts or wherever you listen to podcasts.

Transcript

Martina: ¡Hola listeners! For this special season of the Duolingo Spanish Podcast, we’ll be revisiting some of our favorite stories from Indigenous communities across Latin America! Throughout the region, these communities have kept their customs and traditions alive for hundreds of years. To this day, they remain resilient and bold, reshaping the world as we know it. Today, we’ll travel to the mountains of Perú, to hear an episode from November 2021, featuring Javier Gamboa. He has transformed the lives of hundreds of Quechuan children through books, but it all started unexpectedly. Keep listening to hear his story, and stay tuned until the end for an update from Javier himself. Now, onto the episode.

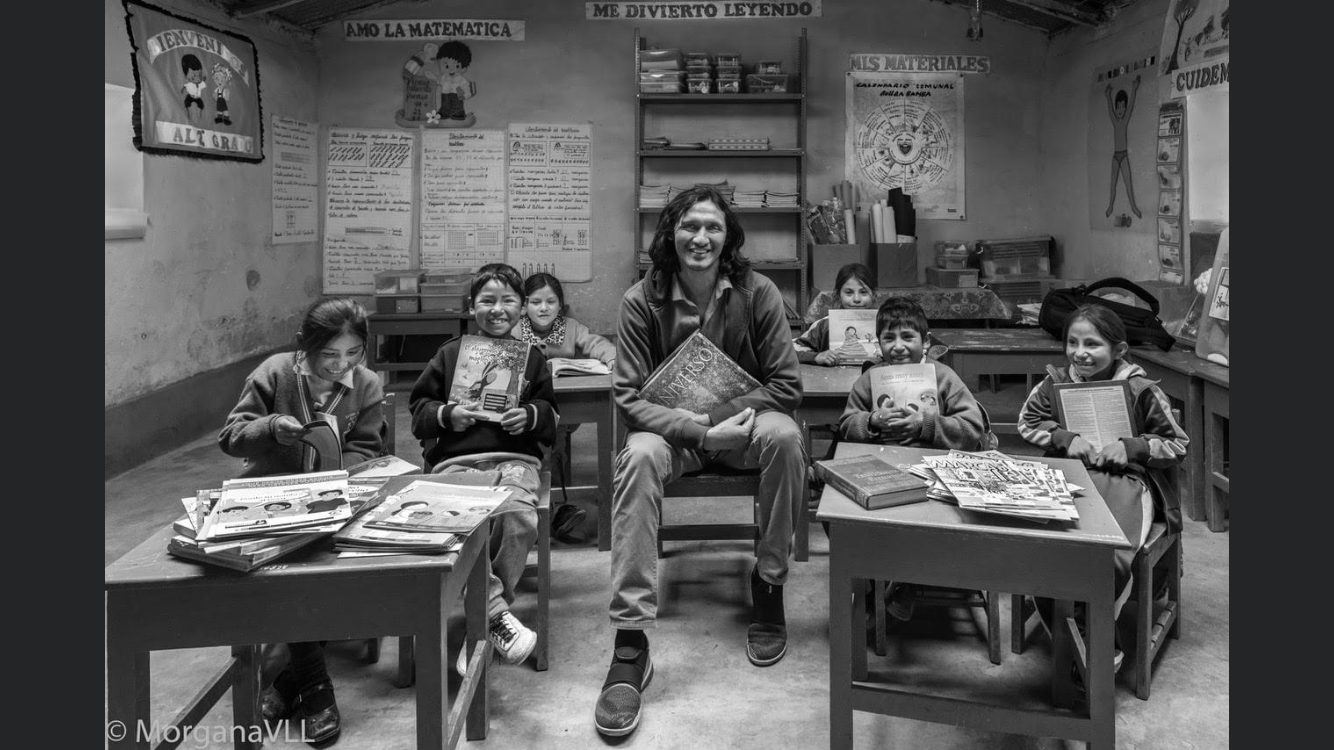

Martina: In May of 2013, Javier Gamboa was visiting Ccollccabamba, a rural village in one of the poorest areas of Peru. He was 47 years old and a photographer from Lima. On this trip, he was taking several bags of school supplies to the only school in town.

Javier: Esa era la única escuela en Ccollccabamba. Tenía doscientos alumnos de todas las edades y muchos venían de pueblos cercanos. La mayoría era gente con pocos recursos. Yo fui a la escuela a hacer una donación y hablé con el director. Antes de irme, le pregunté: “¿Qué libros están leyendo los niños?”.

Martina: The school’s director looked at him and said, “They can’t read anything because there aren’t any books here.” Javier was shocked. He asked how that was possible.

Javier: ¿No hay libros en la escuela? ¡Eso es imposible! Él me dijo que había una pequeña biblioteca y fuimos a verla juntos. Era un espacio muy pequeño y solo había un estante. No había más de veinte libros.

Martina: Javier browsed the books on the shelf. They were all very old and worn. He wondered who would read them.

Javier: Le dije al director: “Esto no es posible. Te prometo que el próximo mes voy a regresar con mil libros”. Él no me creyó y, en realidad, hasta yo me fui de allí con una sensación extraña porque… ¿dónde iba a encontrar mil libros?

Martina: Bienvenidos and welcome to the Duolingo Spanish Podcast. I’m Martina Castro. We’re dedicating this season to you, our listeners. Over the last 12 seasons, you’ve written to us by email and social media, you’ve called and left us voicemails with wonderful suggestions for stories. So, this episode, like the rest of this season, comes from your ideas. Like this one from Sue Lee Anderson in New Zealand:

Sue Lee: I have attached an amazing story that I hope you will be inspired to investigate for a podcast. Javier and I met in 2016. I was touched by his selfless and focused drive to bring hope to people who had been forgotten.

Martina: Thank you so much for your suggestion, Sue Lee. In today’s episode, we’re heading to Peru to learn more.

As usual, the storyteller will be using intermediate Spanish and I’ll be chiming in for context in English. If you miss something, you can always skip back and listen again. We also offer full transcripts at podcast.duolingo.com.

Martina: Javier was born in Lima, the capital of Perú. But ever since he was little, he had heard his parents tell stories about their hometown, called Poma. It’s a tiny village in the middle of the Andes. And it’s so remote, it can only be reached on foot.

Javier: Yo le digo “el pueblo perdido de los Andes” porque no está en los mapas. Se encuentra en Ayacucho, una de las regiones más humildes en Perú.

Martina: Like many people from the rural regions of Perú, Javier’s parents belonged to a Quechuan community. It’s part of a large and diverse set of Andean indigenous groups, whose mother tongue is Quechua.

Javier: Mis padres no hablaban muy bien el español. Su lengua materna era el Quechua. Pero había algo más… mi mamá no sabía leer ni escribir, ella era analfabeta.

Martina: Javier’s parents made it their number one priority to offer their three children a good education. Javier felt like it was his duty to study since his mother never had the chance.

Javier: En la escuela a veces me pedían la firma de mi mamá en los cuadernos o en alguna nota, pero como ella no sabía escribir, solo hacía una letra equis. Yo tenía que leerle toda la información. De niño, eso nunca me pareció extraño, era algo normal.

Martina: As a kid, Javier used his mother’s situation to his advantage when he wanted to get out of doing homework and instead go outside and play.

Javier: Mi madre era muy estricta. Siempre me decía que si quería ir a jugar con mis amigos, primero tenía que terminar mis tareas. Yo hacía líneas o círculos y luego le mostraba el cuaderno. Como ella no sabía leer ni escribir, me creía y yo podía ir a jugar. Ahora que pienso en esos momentos veo la importancia que mi mamá le daba a la educación.

Martina: Javier’s parents had left their hometown in the 1970s to pursue better economic opportunities in Lima. But later, when their children were grown up, they decided to move back. Javier was 30 years old at the time, and working as a photographer in Lima.

Javier: Ellos decían: “No nos queremos morir en la ciudad de Lima viendo televisión. Queremos volver a nuestros orígenes y tener una nueva vida”. Me pareció algo fantástico, así que los ayudé.

Martina: So in the year 2000, Javier visited his parents in their village of Poma for the first time. To this day, there are no more than 50 residents. It’s very different from the metropolis where Javier grew up.

Javier: Poma es un pueblito que está sobre una montañita, cerca de otras montañas. Llegar ahí es toda una aventura. Primero, hay que hacer un viaje de veinticuatro horas en autobús y después, solamente se puede llegar a pie o en caballo. Las casas son muy frágiles.

Martina: Javier planned to stay 15 days, during the springtime harvest. But he ended up staying for four months.

Javier: En Poma me sentí libre. Estaba cerca de la naturaleza y respiraba aire puro. Me encantó trabajar en el campo, cosechar papas, quinoa, trigo y estar con los animales. Mis ancestros eran de esas tierras y yo pertenecía allí.

Martina: Javier visited often and took a lot of photos on his trips. He came to appreciate the region's beauty. But over time, he also saw why his parents had left to look for better opportunities in Lima.

Javier: Ayacucho, la región donde se encuentra Poma, es una zona sin recursos. Ver eso es muy duro e injusto. La mayoría de las casas en la montaña no tienen ni luz ni agua. Los hospitales no están en buenas condiciones y las escuelas no tienen ni siquiera lo básico para poder enseñarles a los alumnos.

Martina: In 2010, during one of his many trips to Poma, Javier was walking by the only school in his parents’ village. It was the start of the new school year, and Javier wanted to check it out.

Javier: Cuando llegué, vi que había un solo maestro con quince niños y niñas. Hubo algo que me sorprendió mucho: los alumnos no tenían cuadernos para escribir, solo tenían hojas de papel que el maestro les daba. Yo fui a hablar con el maestro y le pregunté: “¿Por qué no tienen cuadernos?”. Y él me respondió: “Porque sus padres no tienen dinero para comprarlos”.

Martina: Javier had always known that education in Poma was limited since his mother never learned to read or write. But seeing a school with so few resources with his own eyes…Javier was stunned. And Poma was just one of hundreds of rural towns in the same situation.

Javier: En la mayoría de los pueblos rurales como Poma, solo hay una escuela primaria pequeña. No hay escuelas secundarias. Para seguir estudiando, a menudo los chicos tienen que ir a otros pueblos y para llegar allá, tienen que caminar por horas. Esa es la razón por la que generalmente ellos abandonan los estudios.

Martina: After that first visit to the village school in Poma, Javier decided that on his next trip, he would bring school supplies for the students. It took him longer than expected to return, but he eventually brought back two bags filled with notebooks and pencils.

Javier: En abril de 2013, regresé a Poma con cuadernos y lápices. Pero cuando llegué a la puerta de la escuela, vi que ya no existía. ¡La escuela había cerrado! ¿Qué había pasado? ¿Y qué iba a hacer con todas las cosas que había traído?

Martina: When Javier found out the school in his parents’ village had shut down, he still wanted to donate the school supplies to children who needed them. So he decided to visit a different school in the next town over, called Ccollccabamba. It was a three hour walk to get there, and even though it was larger than his parents’ town, it still had only one school.

Javier: Yo llegué a la escuela de Ccollccabamba y hablé con el director. Él me dijo que tenían doscientos estudiantes de todas las edades y de otros pueblos. Incluso había gente que vivía antes en Poma, y que había decidido irse a vivir allá. Por eso, la escuela ya no existía.

Martina: As they talked, Javier asked the school’s principal a bunch of questions. He wanted to know how the school operated, what the students were learning. Right before he left, he asked what they were reading. That’s when he discovered the school didn’t have a library.

Javier: Yo no lo podía creer. La biblioteca era un cuarto muy pequeño y tenía poco más de veinte libros viejos y repetidos. Yo estaba muy preocupado y sorprendido.

Martina: Javier was upset. First the school in his parents’ village was closed down. Now, students in this school in Ccollccabamba had no books. Without thinking, Javier blurted out that in one month, he would bring one thousand books to the library. The principal looked at him doubtfully. He told Javier that he had been promised many things, many times, and usually they were just that — empty promises.

Javier: Para mí también fue difícil de creer. ¿Dónde iba a encontrar mil libros? Pero mi filosofía de vida es: “Sentir, pensar, actuar”. Así que tenía que hacer algo.

Martina: Javier started the long trip back to Lima. During the 24-hour trek, he went over everything in his mind. He thought about his own personal book collection. It had just 50 books, not enough for the children at school. He had no idea how he would get the rest. But then, with just a few hours left in the journey, he did get an idea.

Javier: Yo trabajaba como fotógrafo en diez academias de baile y cientos de niñas, jóvenes y adolescentes iban a esas academias. Si cada chica hacía una donación, yo podría obtener la cantidad de libros que necesitaba.

Martina: As soon as he got to Lima, Javier contacted the directors of all the dance academies he worked with. He explained his idea: He would ask each dance student to donate a book for the school library in Ccollccabamba. The directors told him they thought his idea was fantastic.

Javier: Pusimos cajas en las entradas de las academias. Los días pasaban y las cajas se llenaban más y más. ¡No lo podía creer!

Martina: In just four weeks, Javier managed to collect 983 books.

Javier: Yo estaba muy feliz. Llevé todos los libros a mi casa, los clasifiqué y los puse en quince cajas diferentes. Lo más difícil iba a ser financiar el viaje de los libros porque tenía que pagar extra por las cajas. No tuve otra opción y pagué con mi propio dinero para enviarlos en autobús a Ccollccabamba. Luego, yo los iba a llevar en persona a la escuela.

Martina: When Javier showed up at the school with all the boxes of books, the school’s principal could not believe it. He rang the bell, calling all 200 students to assemble. Then, the principal introduced Javier and announced he had brought a gift.

Javier: Yo empecé a abrir las cajas y algo hermoso ocurrió. Los niños se lanzaron sobre ellas, tomaron los libros y empezaron a leerlos inmediatamente. Yo nunca había visto chicos tan emocionados con libros. ¡Fue increíble!

Martina: When Javier saw the children so excited about reading, he became so overwhelmed with emotion, that he found himself making another big promise.

Javier: Les dije: “Voy a regresar el próximo mes y les regalaré una mochila con un cuaderno a todos los alumnos que lean al menos un libro”. Los niños empezaron a celebrar. ¡Fue muy emocionante para mí!

Martina: In Lima, Javier received a donation of 200 backpacks and notebooks from a friend who worked in a bank. The next month, when he returned to the school, Javier was shocked.

Javier: Cuando regresé con los cuadernos y las mochilas, sentí una emoción muy grande otra vez. Había dibujos acerca de los libros en todas las paredes de la escuela. Los niños corrían a hablarme de los libros que habían leído. ¡Muchos de ellos habían leído más de uno!

Martina: Javier thought of his parents and how happy they would be to see the school in Ccollccabamba full of books. Sadly, his mother had passed away a few years earlier. Javier’s father, on the other hand, was so proud that he wanted to visit the new library himself. But he suddenly became very sick, and Javier had to take his father back to Lima.

Javier: En ese tiempo, mientras cuidaba a mi papá que estaba muy enfermo, llamé al director de la escuela y le pregunté si era posible ponerle el nombre de mi papá a la biblioteca. Él dijo que sí; se llama Biblioteca Fructuoso Gamboa. Se lo dije inmediatamente a mi papá y se sintió muy emocionado. Él quería recuperarse y salir del hospital para poder ir a ver la biblioteca con su nombre.

Martina: By this point, Javier’s father was so ill, he was in the hospital. Even though he was having difficulty breathing, he wanted to keep talking about his son’s literacy project.

Javier: Él respiraba muy mal, pero me dijo: “Javier, quiero ir al pueblo a ver la biblioteca, pero ya no puedo”. Le dije: “Papá, tranquilo, descansa”. Y, pocos minutos después, él murió.

Martina: After his father passed away and the new school library opened in Ccollccabamba, Javier had another idea. He wanted to create a project that went beyond book donations — something that would reach not just one school, but many.

Javier: Los estudiantes debían tener un rol activo en este proyecto y eso era muy importante para mí. Los alumnos que recibieron los libros ahora podían dárselos a otros estudiantes.

Martina: Javier’s idea was to have older students in Ccollccabamba travel to nearby towns, to check on the condition of those school’s libraries. They would serve as literacy ambassadors and encourage the children in other schools to read. To participate in the program, students had to complete a reading challenge, or desafío de lectura, of reading at least a dozen books.

Javier: Al director le encantó la idea y decidimos compartirla con los chicos. Yo les dije: “Además de entregarles los libros a esos alumnos, ustedes tienen que hablarles de la importancia de la lectura, y, para eso, tienen que leer más libros”. ¡Fue impresionante! Los chicos desarrollaron una adicción por la lectura. Y fue así como en agosto de 2013 el primer grupo de alumnos fue a visitar las escuelas cercanas.

Martina: The older students traveled to 18 different schools throughout the region. When they came back, they told Javier what they found.

Javier: Los niños me dijeron que no había casi nada en las bibliotecas. ¡Necesitaban dieciocho mil libros! Mil para cada una de las escuelas. Una vez más, me sentí paralizado. ¿Dónde íbamos a encontrar todos esos libros?

Martina: That’s how Javier came to launch his largest literacy project to date…starting with a Facebook page called: “Libros para crear oportunidades,” or “Books to create opportunities.”

Javier: “Libros para crear oportunidades” tiene un significado muy especial. Cuando lees un libro, tu mente trabaja y reacciona de otra manera y tú mismo puedes crear tus propias oportunidades.

Martina: Javier ran a campaign through the group’s Facebook page, and it was a success! In just three months, Javier reached his goal: 18,000 books, with donations from across Peru.

Javier: Alquilamos camiones para poder llevar los libros porque muchos pueblos estaban muy lejos.

Martina: At every school he visited, the excitement from the children and teachers affected Javier deeply.

Javier: Cada vez que iba a una escuela me sentía muy emocionado. En general, los niños y niñas viven con muy pocos recursos. Sin embargo, ver sus caras cuando recibían los libros era algo impresionante y me daba la energía para seguir trabajando en el proyecto.

Martina: One day, some girls from the school in Ccollccabamba asked to talk with Javier. They had an idea of their own.

Javier: Las niñas me dijeron que los fines de semana la escuela estaba cerrada y no tenían acceso a los libros. Ellas querían construir otra biblioteca comunal fuera de la escuela para poder leer durante los fines de semana.

Martina: Javier thought it was a great idea. Most of all, he was proud that the girls themselves wanted to promote reading in their community, including people outside the school and their own families.

Javier: Los libros despertaron mucho más que la lectura. Se transformaron en un motor para avanzar dentro de un sistema educativo tan defectuoso. Nunca imaginé que esto iba a suceder.

Martina: Today, as Javier’s literacy project continues to grow, he still thinks about his mother, who never had the chance to learn to read.

Javier: Mi mamá nos dejó en 2011 y no pudo ver mi proyecto. Yo siempre me pregunto: “Si mi mamá hubiese tenido esta oportunidad y hubiese aprendido a leer, su vida habría sido muy diferente”. Por esta razón, mi objetivo es que cada escuela rural y pobre de Perú tenga su propia biblioteca. ¡Y no voy a parar hasta lograrlo!

Martina: Javier Gamboa continues to promote literacy through his nonprofit “Libros para crear oportunidades”. And there’s been even more progress since we first heard his story in 2021. He left us a message via Whatsapp, so he sounds a bit different from his original recording.

Javier: Hola, soy Javier Gamboa. Qué gusto volver a estar por aquí. Me gustaría contarles que desde el 2021 armamos tres nuevas bibliotecas, pero ahora estamos trabajando en un proyecto muy importante.

Martina: Javier and his team have started a new project to train teachers. And they’re building new housing near schools so that students who live in remote mountain villages can have greater access to education.

Javier: Muchos chicos que viven en estos pequeños pueblos deciden estudiar en la universidad. Para mí eso es una gran satisfacción.

Martina: Thank you, Javier! It’s so great to hear from you! We are rooting for you and your students.

This story was produced and adapted by Tali Goldman, a journalist and writer based in Buenos Aires.

We'd love to know what you thought of this episode! You can write us an email at podcast@duolingo.com and call and leave us a voicemail or audio message on WhatsApp, at +1-703-953-93-69. Don’t forget to say your name and where you are from!

If you liked this story, please share it! You can find the audio and a transcript of each episode at podcast.duolingo.com. You can also follow us on Apple Podcasts or on your favorite listening app, so you never miss an episode.

With over 500 million users, Duolingo is the world's leading language learning platform, and the most downloaded education app in the world. Duolingo believes in making education free, fun and available to everyone. To join, download the app today, or find out more at duolingo.com.

The Duolingo Spanish podcast is produced by Duolingo and Adonde Media. I’m the executive producer, Martina Castro. Gracias por escuchar.

Credits

This episode was produced by Duolingo and Adonde Media.

![[Facebook]](./theme/images/share-facebook.svg)

![[Twitter]](./theme/images/share-twitter.svg)

![[LinkedIn]](./theme/images/share-linkedin.svg)